Introduction: Digital Reform

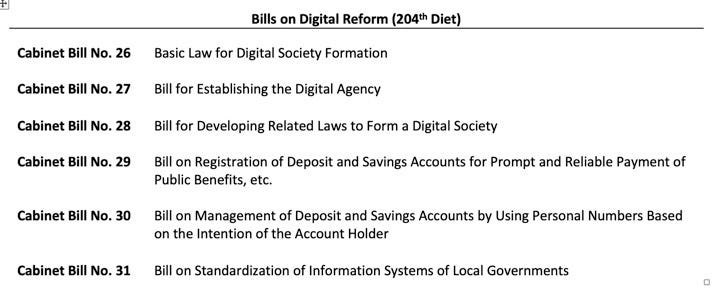

On May 12, 2021, the upper house of the Japanese Diet passed the ‘Bill concerning Digital Reform,’ which included six different bills introduced by the Cabinet Office and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC). This legislative package seeks to deliver Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s campaign promises to establish a ‘Digital Agency,’ reform data governance, and digitalize public service.

Source: Cabinet Legislation Bureau (https://www.clb.go.jp/)

This post provides background on Japan’s efforts at digitalization, a summary of the new laws, and an analysis of the Japanese Digital Reform.

Background: Japan’s Digitalization Paradox

Japan has been known to be a leader in the fields of technology and electronics. However, Japan has surprisingly fallen behind in adopting digital technology.

According to a recent report by McKinsey and Company, Japan ranks 27th in digital competitiveness. The penetration rate for e-commerce (9%), healthcare (5%), and finance (6.9%), as well as the percentage of citizens using digital government applications (7.5%), are all in single digits. Last year, the reporting that 95% of businesses in Japan still use fax machines became a rallying cry for a digital reform in Japan.

In recent years, the Japanese government has made substantial efforts to become competitive in the digital space. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration put forward the concept of Society 5.0 which was a key piece of “Abenomics,” the national strategy that sought to revitalize both the Japanese economy and society. Society 5.0 presented the vision of leveraging the Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things, or robotics, to address the challenges that Japanese society and economy faced. Tokyo then developed national strategies for enhancing digital competitiveness around Society 5.0. For instance, Tokyo created the Strategic Council for AI Technology to coordinate AI-related policies across key ministries and released the AI Technology Strategy, which outlined Japan’s AI R&D and industrialization roadmap.

At the same time, Tokyo sought to take Society 5.0 abroad. Abe introduced the concept of Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) at the World Economic Forum in 2019 and launched the ‘Osaka Track’ within the G20 meeting in Japan. Japan also joined Canada-led Global Partnership on AI as one of the founding members in 2020. Domestically and abroad, Tokyo has shown the determination to play a leading role in the digital space.

However, the implementation of Japan’s digitalization agenda has not moved as quickly as expected, which became even more apparent during COVID-19. Citizens applying for pandemic relief programs faced undue delays as a result of a lack of digitization in the delivery of public service programs. The My Number card, a digital program introduced in 2016 with the intent of avoiding such processing delays still only saw 16% of Japanese residents to use the system as of April 2021.

Suga’s election in 2020 saw digitization return as a national priority with the suggestion of a number of digital reform bills.

What do the new laws do?

There are numerous items introduced in these Digital Reform bills. This section highlights the three most significant elements: digital agency, data governance, and digitalization of public service.

Establishment of a Digital Agency

Broadly, the proposed Digital Agency is expected to function as a ‘control tower’ to digitalize Japan’s public service with significant powers over ministries, agencies, and local governments. On more concrete and immediate deliverables, the Digital Agency is expected to push for universal adoption of the My Number System and improve data and systems interoperability within government. The Agency is expected to hire more than 500 ‘technologists’ for its operations.

Data Governance

The Digital Reform package proposes to centralize the governance of data under the Personal Information Protection Commission, as well as to consolidate three laws (Act on the Protection of Personal Information, Act on the Use of Numbers to Identify a Specific Individual in Administrative Procedures, and Act on the Protection of Personal Information Held by Administrative Organs) upon a review of the personal information protection system.

Personal data will be labelled into ‘national,’ ‘private sector,’ and ‘local government’ categories and the national government will provide a unified set of guidelines on data anonymization and sharing. These measures aim to allow the flow of data between the national government, local governments, and the private sector. Further, in accordance with the GDPR, data for academic research will be exempted from the regular requirements.

Digitalization of Public Service

This legislative package also seeks to eliminate physical paperwork and bureaucratic red tapes through the My Numbers System. The new laws would enable Japanese residents to access public services (e.g., obtaining government certificates) at local post offices through the My Numbers System. Individuals would also download the My Numbers mobile app to verify their identities and access public services. In addition, responding to the COVID-19 relief payment fiasco, the new laws allow the linkage of the My Numbers service with banking information to facilitate the efficient distribution of payments from the government.

Analysis

First, Japan’s private sector, which boasts a world-class robotics industry, electronics and automobile manufacturers, and systems integrators, is likely to move to embrace digitalization at a faster pace. The McKinsey report underscores that government agencies have often played the role of a pioneer or first-mover in new sectors in Japan and that the private sector had been waiting for signs from the government to take more aggressive steps in digitalization.

Second, the attempt to facilitate the free flow of data between different ministries, agencies, and local governments will be of interest for Canada, as it grapples with similar problems within its federal system. There are concerns that Tokyo’s attempt to create a national standard for all levels of government might create unexpected loopholes, considering that some local governments have very stringent data protection policies that might have be loosened up. Also, others are worried that the Personal Information Protection Commission might not be well-equipped to address increased responsibilities as the sole entity overseeing data privacy.

Finally, it will be important to follow the public trust in these new measures. There certainly are some institutional issues that have undermined the public trust in digital services by the government, but such a low uptake of digital solutions not just in government services but also in e-commerce, digital payment, and healthcare for a country that is known to be tech-savvy has been attributed to deeply ingrained cultural attitudes. The efforts of the Suga administration to turn things around and build public trust in digital services, if successful, will provide useful insights for other countries grappling with similar challenges.